Scandia Festival

2000 - coming in February

by Fred Bialy

The upcoming annual Scandia Festival weekend workshop will take place

February 1920, 2000, at Hermann Sons Hall in Petaluma, CA. The focus

of the dance teaching will be Valdres springar, taught by Marit and Terje

Lundemoen from Valdres in Norway. Accompanying them will be a hardingfele

player from their home district who is yet to be determined. Swedish

fiddle greats Kalle Almlöf and Jonny Soling will be on hand to teach

fiddling during the day and play for dancing Saturday and Sunday evenings.

Marit and Terje Lundemoen began teaching at a young age in Valdres and

have demonstrated their ability with a first place finish at the 1981 Landskappleik,

an annual national competition for folk music and dancing. They won

second place at the 1993 Landskappleik. This will be their second

visit to California, having previously taught at Scandia Camp in 1991 together

with their teachers, Knut and Berit Steinsrud.

Kalle Almlöf, born in Malung (Western Dalarna) in 1947, has been

playing fiddle since he was a small boy. His early training was from

local fiddlers. He subsequently attended the university in Stockholm

where he attended the first course designed for folk musicians. Over

the years he has delved deeper into the music traditions of western Dalarna

through study visits to older fiddlers and by researching various tune

collections from the region. His playing style has served as an inspiration

for many fiddlers. Since 1978, he has been teaching a one semester

course in folk fiddling at the folkhögskola in Malung. Kalle

has also studied violin making and is a skilled instrument builder and

repairer.

Jonny Soling, born in the Dalarna town of Orsa in 1946, did not start

playing fiddle until he was 25. He learned rapidly and received recognition

as a riksspelman after only two years. His music education at the

universities in Stockholm and Gothenburg provided the foundation for what

has become a highly influential career as a teacher of fiddle playing and

folk music. In 1979 he started teaching a two semester course in

folk fiddling at the folkhögskola in Malung. In addition, he

continues to teach numerous weekend and week long summer workshops for

both adults and children. This trip will be his sixth tour to the

United States. During a visit to Minneapolis in 1988, he was a guest

on the radio show “A Prairie Home Companion.” This will be Kalle

and Jonny’s third appearance at Scandia Festival, having been featured

fiddle teachers in 1991 and 1994. Jonny was also here with Pål

Olle Dyrsmeds in January of 1983, and the two were at Scandia Festival

in February of 1984.

Cost of the full weekend for both dancers and musicians will be $80,

which includes classes on Saturday and Sunday and dance parties on Friday,

Saturday, and Sunday evenings. Preregistration is required for the

dance workshops. Dancers of all levels are welcome, although prior knowledge

of Valdresspringar is recommended. A good balance between the

number of men and women dancers will be attempted. During teaching,

dance partners are changed frequently.

The number of dancers participating is limited due to space considerations,

so early registration is encouraged. Men are especially encouraged

to register early, because the number of women dancers admitted is usually

determined by the number of men attending. Evening dance parties

are open also to those not registered for the daytime workshops. Fiddle

instruction will be at an intermediate and advanced level in two simultaneous

groups. Beginners may attend at a reduced price. Preregistration

for fiddle workshops is requested. Part time attendance at the fiddle

workshops is possible (paying on a session by session basis).

For registration information for dance workshops, contact Mary Korn

at (510) 5279209. For fiddle workshops, contact Fred Bialy at (510)

215-5974. §

It’s That Time of Year Again…

Yes, it’s that time of year again, when thoughts turn to gifts and taxes.

And memberships in various organizations. Please take the time to look

over the questionaire in our inside back cover to make sure your address

information is up to date. While you’re at it, think about what you’d

like to see the organization do for you, and what you might do for us.

Sometimes it takes awhile to organize events, but your suggestions are

all considered, and often acted upon. Also, take a look at the article

concerning event organization on page 4.

And last but not least - don’t forget to donate. We still have

not reached our goal of paying for the newsletter by donations; we’d

like to keep it free to all who’d like to receive one.

§

The Kalevala's 150th Anniversary

This year, 1999, is the 150th anniversary of the publication of the

Finnish epic poem, the Kalevala, in its final expanded form. The

early years of the nineteenth century brought an awakening of national

feeling to Finland, and young students began to collect the old poems,

songs, and stories of the common people. One of them, Elias Lönnrot,

put these together to make a dynamic whole, first published in 1835.

In 1849 he published an expanded version, which is the version most often

used and translated today. It is this anniversary which has been

celebrated this past year. Anja Miller, a Finn living in the San

Francisco area, has written a brief article (see pg. 2) about the Kalevala

and its importance to the Finnish people. If you are interested,

contact her at the address at the end of her article.

What is the Kalevala?

by Anja Miller

Most people who appreciate Scandinavian culture know about the Icelandic

Edda, the stories of Norse heroes like Odin and Thor. Often these

characters have their counterparts in Greco-Roman culture (Zeus/Jupiter,

Ares/Mars). They are central in pre-Christian epics, collections

of stories, verbalized sets of myths and beliefs shared by people with

the same kind of culture. The characters (divinities) in the stories

always possess a mixture of human and superhuman qualities. They

are archetypes, as the psychologist Jung would call them.

The

archetypes of the Finns reside in a different environment, in their own

folk poetry. Originally oral songs and stories, Kalevala poetry is

said to have developed among the protoFinns living around the Gulf of Finland

about 3000 years ago. The best known epic collection of these songs

is called the Kalevala, first published in 1835 by a traveling country

doctor named Elias Lönnrot. In addition to the stories in his

Kalevala, however, a wealth of other folk poetry exists, including lyrical

and ritualistic songs and spells. These were naturally frowned upon

by Christian authorities. Under the weight of the political rule,

first of Sweden for 700 years, and then of Russia for 100 years, this rich

folklore of the Finns, along with their language, was suppressed.

The publication of the Kalevala was a milestone, an impetus for a national

awakening still being felt today.

The

archetypes of the Finns reside in a different environment, in their own

folk poetry. Originally oral songs and stories, Kalevala poetry is

said to have developed among the protoFinns living around the Gulf of Finland

about 3000 years ago. The best known epic collection of these songs

is called the Kalevala, first published in 1835 by a traveling country

doctor named Elias Lönnrot. In addition to the stories in his

Kalevala, however, a wealth of other folk poetry exists, including lyrical

and ritualistic songs and spells. These were naturally frowned upon

by Christian authorities. Under the weight of the political rule,

first of Sweden for 700 years, and then of Russia for 100 years, this rich

folklore of the Finns, along with their language, was suppressed.

The publication of the Kalevala was a milestone, an impetus for a national

awakening still being felt today.

This poetic song tradition uses an archaic trochaic tetrameter, an unusual

poetic rhythm familiar to Americans from Longfellow’s poem, “Hiawatha.”

The uniqueness of the content and language of Kalevala poetry lies above

all in its very close connection with nature. We Finns often

say that we are “the last people to come down from the trees,” and we advise

our children to “listen to the tree that you live under.”

| Kamanat kohottukohot |

Pihtipielet välttyköhöt, |

| lakin päästä ottamatta. |

ovet ilman auetkohot |

| Kynnykset alentukohot |

vieraan tullessa tupahan, |

| kengän kannan koskematta. |

astuessa aimo miehen. |

The other difference that sets apart the Kalevala is its definition

of heroism.

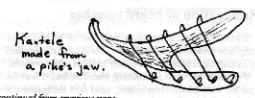

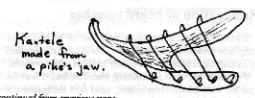

The power of Väinämöinen, the ageless hero (not god),

lies in his wisdom and song—words, not violence and war. When he sang and

played his kantele, which he first made of the jawbone of a giant pike

and the hair of a maiden, all the creatures of the forest and all the people

came to hear him, and he made them weep with emotion. He also lusted

after young girls but lost them all.

Other main characters in the Kalevala epic include the blacksmith Ilmarinen,

the archetype of a skilled workman. He forged himself a golden bride (whom

he found too cold in bed!) and showed himself a true master by forging

the Sampo, a magic mill, the source of all the wealth of any nation that

possessed it. Alas, the Sampo was lost in the sea in a battle with

Louhi, the powerful and wily female ruler of Pohjola (the North).

Then there’s the young daredevil Lemminkäinen, favorite of the girls,

whose mother brings him back from death in one of the most moving scenes

of the epic.

Why is the Kalevala so important to the Finns even today? It is the

most enduring symbol of the creative spirit and closeness to nature of

all Finns, a national treasure that resonates in all the basic aspects

of ethnic identity, shared values, and belonging. In school we are

not only taught the rich, albeit currently archaic, language of the poems,

but also encouraged to carry on the tradition by writing our own whenever

the occasion seems to call for it. (The last time I remember doing

that was when one of my favorite dance teachers had a mysterious back ailment.

He may say the antibiotics cured him, but I believe my spell played its

part as well!)

Among the world’s epics the Kalevala is recognized as possessing universal

significance regardless of language, race, or cultural features.

Translations of Lönnrot’s collection run into the hundreds, including

three versions in English. The best one, in my opinion, was done by Finnish-American

Eino Friberg not too long ago. A wonderful illustrated short version

for children is The Magic Storysinger by M.E.A. McNeil of Mill Valley.

Another tangible influence of the Kalevala can be seen in Finnish art,

particularly the paintings, murals, and book illustrations by Akseli Gallen-Kallela.

On your next visit to Helsinki, I recommend a visit to the Atheneum (Finnish

national gallery) and the National Museum for his frescoes of Kalevala.

And in music, not only fiddler polkka tunes hark back to Kalevala, but

so do classic works by Sibelius (The Karelia Suite), Kuula, and many other

composers. Enough about Kalevala? If you want to know more, feel

free to contact me at anja_miller@compuserve.com.

§

Scandia Camp Mendocino

Scandia Camp Mendocino in northern California will feature the music

and dance of Småland, Sweden and Gudbrandsdal, Norway from June 9

- 16, 2000. Magnus Gustafsson, Ulrika Gunnarsson, Toste Länne,

Anders Svensson, and Marie Länne-Persson return to the US to teach

Slängpolska from Småland, and fiddler Ivar Odnes from Gudbrandsdal

along with American dancers Nobi Kuroturi and Roo Lester will teach Springleik

from Vågå in Gudbrandsdal.

The music staff will include Fred Bialy, Music Director, Loretta Kelley

teaching Telemark hardingfele tradition, Bruce Sagan teaching Nyckelharpa,

Peter Michaelsen leading allspell and Sarah Kirton reviewing tunes

and teaching Valdres hardingfele tradition.

For more information and to get on the mailing list, write to: Scandia

Camp Mendocino, 393 Gravatt Drive, Berkeley, CA 94705, or Roo Lester

(DancingRoo@aol.com) or (630) 920-0159 [Central time zone]. Information

is also posted on Roo's web page, http://members.aol.com/dancingroo.

Be sure to register early. The size of the dance space and number

of cabins limit the number of campers. An attempt is made to balance

the number of men, women and

couples in the dance program. All applications received before

January 10th, 2000, will be treated equally. §

Newsletter possibilities

Do you have an idea for the newsletter? Would you like to write

an article for it? Review recent recordings? Announce an event?

Your help would be much appreciated. We would like to limit articles

to those of interest to our readership - that is, they should be about

Scandinavian music, dance, or folk culture either in the United States

or in Scandinavia. Articles on modern Scandinavian culture may also

be usable. Contact our editor at (650) 968-3126 or email her at sekirton@ix.netcom.com.

§

Resignation of board member

Patrick Golden, a founding member of NCS and its long-time treasurer,

has resigned. He is looking forward to having more time for his family

and his other projects.

Patrick is not only a founding member, but it was he and his wife, Susan

Overhauser, who first instigated the formation of NCS in 1988. They’ve

guided it through attaining incorporation and non-profit status, and were

a vital driving force behind the projects of our first years as an organization.

Patrick has given freely of his energy, drive, ideas, and expertise, all

of which will be sorely missed. He stays on in an advisory role to

the treasurer, as needed. Jim Little has taken over the treasurer's post.

§

Have an event idea?

You can make it happen!

NCS could sponsor more special events with your help. All we need

is good ideas, and people willing to be the “driver” and make it happen.

We have (or can find) people who will help. We even have funds to

help cover expenses if necessary. If you have an idea for a workshop,

dance, concert, etc., let’s work together.

If you have an idea, are able and willing to organize it but need help,

ask an NCS Board member to help you put together a short proposal explaining

your idea and what help you need from NCS. Help from NCS could include

any or all of the following: money, people to do things, people to provide

ideas and feedback (like locations and scheduling), and insurance.

The proposal does not have to be elaborate; just a short description

of what you’re thinking of doing and what you’d need from NCS to make it

happen. There’s a proposal template and more detailed guidelines

on the NCS website at http://members.aol.com/jglittle/ncsproposal.html.

There are also folks around who can help you estimate costs and preparation-time

requirements.

If you have an idea, but for whatever reason can’t organize it yourself,

we may still be able to help. Just talk to any NCS Board member.

(see About NCS for phone numbers and e-mail adresses) We’ll

try to find someone else to take the lead.

So, don’t let your good ideas remain simply ideas. Let’s turn

them into more of the events we all love to attend. §

Fiddle Tips - Holding the fiddle

by Sarah Kirton

In the last issue I gave some tips for holding the bow and bowing -

this issue it's time to examine holding the fiddle itself. (I'm assuming

you know the basics, so you don't end up holding it upside down, or whatever!)

Holding the fiddle need not cause many aches and pains once the muscles

are used to what they should do. Like holding the bow, holding the

fiddle is an exercise in balance. Let's see what one needs to do.

Without the fiddle, stand straight and hold your arms straight out from

your sides. This creates a plane (remember geometry class) that I'll

call the body plane. Put your arms back down and pretend there's

a string attached to the top of your sternum which is drawing you up.

Let your weight rest a bit more on your heels than on your toes.

Now put your left arm in front of you in fiddle playing position.

Your left shoulder probably moved a bit forward when you put your arm in

front of you. If it didn't, let it move forward to a comfortable

position. We want to stand straight, but we're not in military training.

Notice that when you're standing tall with your weight a bit back, your

arm isn't as heavy as if you slouch. You're using your back and your

weight to form a counter-balance to your arm, easing the

problem of holding it out there for hours on end.

To continue - arm stretched out in front of you, palm facing up

and towards you. The inside of your elbow is also facing up and the

elbow is bent. Your wrist is straight. Let your elbow

hang straight down, regardless of what you've been told about where it

should be. When your hand is relaxed, your fingers curl a bit, and

a connect-the-dot line drawn between their tips probably forms an almost

straight line pointing back at your body. Your thumb is probably

straight and parallel to the plane of your hand. There are two schools

of thought about the elbow position. My classical teachers said it should

be pointing a bit to the right, more or less under the right edge of the

fiddle. This has always been uncomfortable to the point of impossible

for me. I have to admit to ignoring my teachers on this

point (!), and it was a great relief to find another school of thought

(also classical) that says to let it hang pointing straight down at the

floor in a natural, relaxed position. It seems to me that there is

no reason to inject the extra tension needed to pull the elbow toward the

right. The hand and fingers can still curl sufficiently over the

fingerboard to play well.

The

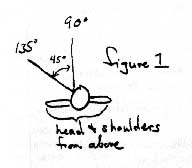

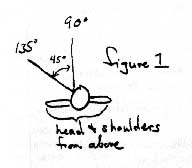

angle of the fiddle to the body plane is another point to cover.

See figure 1. Comfortable angles usually range from just a

little greater than 90° (a bit left of center), to somewhere around

120° (farther left). This may require a compromise between what's

comfortable for you, how long your arms are, and how easy it is to

use your entire bow. Short armed people can use more bow if their

fiddle is closer to that 90° angle. Long armed people find

that as they hold their fiddle closer 90°, it's all too easy to run

the bow tip off the strings on down bows. They'll probably want to

cultivate a larger angle to avoid this.

The

angle of the fiddle to the body plane is another point to cover.

See figure 1. Comfortable angles usually range from just a

little greater than 90° (a bit left of center), to somewhere around

120° (farther left). This may require a compromise between what's

comfortable for you, how long your arms are, and how easy it is to

use your entire bow. Short armed people can use more bow if their

fiddle is closer to that 90° angle. Long armed people find

that as they hold their fiddle closer 90°, it's all too easy to run

the bow tip off the strings on down bows. They'll probably want to

cultivate a larger angle to avoid this.

Let's try this with the fiddle, and refine some things. With the

fiddle neck in your left hand, place the other end of the fiddle (the part

with

the chinrest on it!!) against the left front side of your neck, under your

jaw. (Whether you place it at the “bottom end” of your neck, or higher,

closer to the jaw will vary from person to person. Continue reading,

then experiment to find a good fit for you.) Don't lower your chin

just yet. Balance the fiddle neck with your left hand (don't grip

it, just let it rest there), and let the other end balance (!!) on your

collarbone. Keep your shoulders relaxed, and let the left shoulder

come only as far forward as necessary for you to extend your arm.

Wiggle the fiddle around to find a place where it balances well.

I've never yet seen anyone who doesn't have such a place. The angle

the fiddle sticks out from your body plays a role in this balance, so be

sure to try different angles. You may need to shift which part of

the rounded, body end of the fiddle is against your neck. This can

range from the section where the chinrest is normally attached, to the

center of the fiddle, where the tailpiece is attached. The fiddle

body should be parallel to the floor or tilted just slightly to your right.

How much depends on what's comfortable for you. Once you've found a balancing

spot, move on to the next step - getting the proper left hand hold on the

fiddle neck.

Put your fiddle down a minute. Rub the side of your left index

finger and hand (the side towards the thumb). You should feel a bump

(which you may or may not see) formed by the base knuckle. Remember

where this is.

Balancing the fiddle at your own personal balancing spot, hold the neck

between the upper part of thumb (last joint or higher) and just above your

newly found lump. Keep your wrist straight. Sometimes people

squeeze the neck between thumb and first finger. Don't. Just

let your fiddle rest above (and on!) that lump. Your thumb rests

against the other side of the fiddle neck for two reasons. First,

to give just enough pressure that your fiddle doesn't slip

below the "lump" of your first finger base knuckle, and two, to act

as an anchor point. (We'll talk about this next time.) Your

thumb should be close to straight up and down. It can point a bit

toward the scroll of the violin, but don't let it get much off vertical.

Don't let it slide up and down on the neck. And remember - fiddle

necks are NOT to be strangled! Ever.

You've been thinking that balancing this expensive (or not) instrument

on an almost unseen lump on the edge of your first finger and on your (probably)

lumpy collarbone is fine as long as you don't breathe, but what about real

life? Well, you've got a point. Here's where classical violinists

and fiddlers come to a parting of the ways. If you play classical violin,

you need to shift your hand up and down the neck, and the method used by

many folk fiddlers to hold their instruments will not work for you, especially

while shifting down. But it's more relaxed for the neck and shoulder,

(especially if you've acquired the bad habit of tensing up) and using

the folk method could give you much needed relaxation during passages

using only first position. Folk fiddlers will find that knowing the

classical hold can be indispensable when you need to shift, when you must

play in crowds, or any other time you need a bit more security. The

trick with both methods is to stay relaxed.

There are many opinions as to what is the "only right way" to hold a

violin, and one can become completely confused. Give any new way you run

across a fair trial, and incorporate anything that's useful for you.

Learning to hold a violin is a lifelong process. Your method will

change as your playing improves and your body ages or becomes more coordinated,

and, one hopes, more relaxed about the whole thing.

So - a brief outline of both methods. Hold the fiddle as

above, holding it just tightly enough between the thumb and forefinger

to press it slightly into your neck. That's all that's required for

the fiddler's method. The friction of (naturally) slightly damp skin

at your neck will also help to keep the fiddle from sliding around.

Rest your chin in the chinrest, but read further about this, too.

This adds more stability to your hold. Don’t squeeze the neck with

your left hand - it doesn't take much to shove the fiddle a bit toward

your neck. Not squeezing is one of the important things to learn.

If your finger skin is not overly wet or dry, it could be that just balancing

the fiddle neck will give you all the extra friction needed between skin

and fiddle to press it ever so slightly into your neck. The violinist

needs to do a bit extra. S/he not only rests the chin on the

chinrest, but also adds a little extra pressure with the jaw. I find

it best to get the jaw over the raised edge of the chinrest and then pull

the jaw back toward the neck a little. The fiddle is caught by the

geometry of the jawbone, the neck, and the shape of the chinrest, and one

needn't exert much extra pressure to hold the fiddle. Instead, the

fiddle is wedged into place by geometry and balance. The violinist

should be able to hold the fiddle up with the neck and jaw alone.

(Look Ma! No hands!!) This takes more than a bit of practice.

At first the fiddle will slowly slide toward the center until you decide

you'd better catch it before it clatters to the floor. The natural

thing is to go all tense when trying this. Don't. Since your

left shoulder is slightly forward, it will also help support the violin.

Resist the temptation to move it forward much more, to hunch up, or curl

it forward. Get into these habits, and you'll pay with unnecessary

pain. You'll need to develop some neck muscles to keep the fiddle

wedged into place, but try to keep things as relaxed as possible as you

learn how to hang onto the fiddle with your jawbone. Once you've

developed the right muscles, they won't need to tense up. Resist

the temptation to clench your jaw. In all honesty, it can take

a year or more to learn to do this.

Now for the choice of chinrests and shoulder pads. The only words

of wisdom I have about chinrests are to go to a store and try some out.

Some people like a chinrest that fits over the tailpiece instead of off

to one side. This can also let short-armed folks use the entire bow,

instead of losing out on the use of the last few inches near the bow tip.

Some are thicker, some have higher, lower, or variously shaped “lips” at

the edge. Choose carefully. It may save your needing a shoulder

pad, which are a hassle to use and keep track of.

Shoulder pads (a.k.a. shoulder rests) can be a huge problem. I

myself don't use them. The fastest way for me to literally drop my

fiddle while I'm trying to play is to try one out. But many people

can't seem to balance their fiddle well enough in real life (instead of

the balancing exercise above) to play without one. I also think that

if you can be comfortable without one, it would be nice not to use one.

Although I suspect most people need one, I also suspect people just assume

they (or their students) need one, and never give the no-fuss alternative

a chance. If you decide you need one, try a variety of your friends' shoulder

pads. Then go to a store with a wide variety and which does a lot

of business with string players. A trip into the nearest city can

be well worth it in avoided frustration. Some salespeople are very

experienced at helping choose a shoulder pad that's right for you.

Get the salesperson to show you how to adjust them. Combine this

with a search for the ideal chinrest. Be aware that the "right" shoulder

pad (or chinrest) for you may change as you become more experienced and

as you grow older. (I'm

not just talking about the teenager to adult transition here, but also

about such changes as entering a more relaxed or more stressed few years.)

People

often say shoulder pads help avoid the “need” to hunch the shoulder to

help support the fiddle. That's something you should never do anyway

- the fiddle rests against the neck and on the collarbone, with minimal

help from the shoulder, or it's caught up in the geometry of neck,

jaw and collarbone. The shoulder pad can make the fiddle effectively

thicker, so that catching it under your jaw while it simultaneously rests

against the neck and collar bone may be easier. Some people report

that while they can hold the fiddle up without a shoulder pad, it's enough

easier with it that they prefer to use one. Most people are probably

better off with one, but if you're one of the exceptions, it's worth finding

out.

People

often say shoulder pads help avoid the “need” to hunch the shoulder to

help support the fiddle. That's something you should never do anyway

- the fiddle rests against the neck and on the collarbone, with minimal

help from the shoulder, or it's caught up in the geometry of neck,

jaw and collarbone. The shoulder pad can make the fiddle effectively

thicker, so that catching it under your jaw while it simultaneously rests

against the neck and collar bone may be easier. Some people report

that while they can hold the fiddle up without a shoulder pad, it's enough

easier with it that they prefer to use one. Most people are probably

better off with one, but if you're one of the exceptions, it's worth finding

out.

And now I'll throw in something odd. When I was a child and teenager,

I was very skinny, and was thought to have a long neck. One of my

teachers, concertmaster of a well respected symphony orchestra, told me

I was lucky to have a long neck, since it meant I didn't need a shoulder

pad. Now that I'm older and not exactly skinny, my neck seems to

be short, I'm told that's why I don't need a shoulder pad.

Go figure. Just give both ways a fair trial if you're a beginner,

or are currently dissatisfied.

A lot of folk fiddlers "break" their wrists when they play. That

is, they bend their wrist back so that the palm touches and supports the

neck of the fiddle. Hardingfele players do a variation on this, which we

won’t discuss here. They have reason to do it, you don’t. I

suspect it can also lead to various repetitive motion injuries. Resist

this temptation, if for no other reason than that it restricts finger motion.

Your left forearm, wrist, and hand should make a straight line when seen

from the side (look in a mirror). We'll talk more about this next

time.

And now another practical point. It's difficult to hold the fiddle

and play well if your hands and/or neck are too dry (winter weather can

do this) or too wet (dancing in hot weather or excessive nervousness do

it to me). The tiny amount of "damp skin friction" (for lack of a

better term) needed to hold the fiddle easily just isn't there.

If your hands are too wet, you slide all over the fingerboard, resulting

in out of tune playing, and you constantly feel that you're about to drop

the fiddle. As a result you tense your hand, neck and shoulder, resulting

in muscle cramps and frustration, which of course makes matters even worse.

If too dry, the problem isn’t as bad, but your hand (or at least my hand)

slowly creeps up the neck, again with out of tune results, and squeezing

to try to stay in place. There's also the odd problem of hands that are

just damp enough to be a bit sticky, and you can't slip along the fingerboard

when you need to. I've found that applying (don't laugh) cream antiperspirant

in very, very tiny quantities helps the with wetness and sweat-caused*

stickiness, and hand lotion helps with dryness. Apply it long

enough before playing not to get goo on your fiddle. And beware

- it takes much less antiperspirant than you might think. This

discovery has made my playing life a lot easier - at least when I remember

to apply the proper cream in time.

Well - I've run out of room here. I'd thought to say something

about proper fingering technique, but that will have to wait till another

time.

Comments and questions are more than welcome.

* Need I say that stickiness caused by contact with refreshments or

your dancing partner requires good old-fashioned hand-washing!!

; )

American Scandinavian Music

Sites:

The Northern California Spelmanslag:

http://members.aol.com/jglittle/ncs.html

Nordahl Grieg Leikarring

& Spelemannslag

http://home.att.net/~williamlikens/ngls/ngls.html

The American Nyckelharpa Association:

http://www.nyckelharpa.org

Bruce Sagan’s Scandinavian

Web Site:

http://www.math.msu.edu/~sagan/Folk/sources.html

The Hardangar Fiddle Association

of America

http://www.hfaa.org/

The Skandia Folkdance Society

(Seattle):

http://www.Skandia-Folkdance.org

About the Calendar

A (somewhat) more detailed and up-to-date calendar can be found on the

NCS Webpage at http://members .aol.com/jglittle/ncs.html.

Web and Newsletter calendar submissions should be sent to Jim Little

at 321 McKendry, Menlo Park, CA, 94025, email: james.little@sri.com,

phone: (650) 323-2256 or Sarah Kirton at 330 Sierra Vista Ave. #1,

Mt. View, CA, 94043, email: sekirton@ix.netcom.com, phone:

(650) 968-3126. Suggestions for what to include in a calendar

submission are on our web page. The web page calendar is updated

as material is received. §

The

archetypes of the Finns reside in a different environment, in their own

folk poetry. Originally oral songs and stories, Kalevala poetry is

said to have developed among the protoFinns living around the Gulf of Finland

about 3000 years ago. The best known epic collection of these songs

is called the Kalevala, first published in 1835 by a traveling country

doctor named Elias Lönnrot. In addition to the stories in his

Kalevala, however, a wealth of other folk poetry exists, including lyrical

and ritualistic songs and spells. These were naturally frowned upon

by Christian authorities. Under the weight of the political rule,

first of Sweden for 700 years, and then of Russia for 100 years, this rich

folklore of the Finns, along with their language, was suppressed.

The publication of the Kalevala was a milestone, an impetus for a national

awakening still being felt today.

The

archetypes of the Finns reside in a different environment, in their own

folk poetry. Originally oral songs and stories, Kalevala poetry is

said to have developed among the protoFinns living around the Gulf of Finland

about 3000 years ago. The best known epic collection of these songs

is called the Kalevala, first published in 1835 by a traveling country

doctor named Elias Lönnrot. In addition to the stories in his

Kalevala, however, a wealth of other folk poetry exists, including lyrical

and ritualistic songs and spells. These were naturally frowned upon

by Christian authorities. Under the weight of the political rule,

first of Sweden for 700 years, and then of Russia for 100 years, this rich

folklore of the Finns, along with their language, was suppressed.

The publication of the Kalevala was a milestone, an impetus for a national

awakening still being felt today.

The

angle of the fiddle to the body plane is another point to cover.

See figure 1. Comfortable angles usually range from just a

little greater than 90° (a bit left of center), to somewhere around

120° (farther left). This may require a compromise between what's

comfortable for you, how long your arms are, and how easy it is to

use your entire bow. Short armed people can use more bow if their

fiddle is closer to that 90° angle. Long armed people find

that as they hold their fiddle closer 90°, it's all too easy to run

the bow tip off the strings on down bows. They'll probably want to

cultivate a larger angle to avoid this.

The

angle of the fiddle to the body plane is another point to cover.

See figure 1. Comfortable angles usually range from just a

little greater than 90° (a bit left of center), to somewhere around

120° (farther left). This may require a compromise between what's

comfortable for you, how long your arms are, and how easy it is to

use your entire bow. Short armed people can use more bow if their

fiddle is closer to that 90° angle. Long armed people find

that as they hold their fiddle closer 90°, it's all too easy to run

the bow tip off the strings on down bows. They'll probably want to

cultivate a larger angle to avoid this.

People

often say shoulder pads help avoid the “need” to hunch the shoulder to

help support the fiddle. That's something you should never do anyway

- the fiddle rests against the neck and on the collarbone, with minimal

help from the shoulder, or it's caught up in the geometry of neck,

jaw and collarbone. The shoulder pad can make the fiddle effectively

thicker, so that catching it under your jaw while it simultaneously rests

against the neck and collar bone may be easier. Some people report

that while they can hold the fiddle up without a shoulder pad, it's enough

easier with it that they prefer to use one. Most people are probably

better off with one, but if you're one of the exceptions, it's worth finding

out.

People

often say shoulder pads help avoid the “need” to hunch the shoulder to

help support the fiddle. That's something you should never do anyway

- the fiddle rests against the neck and on the collarbone, with minimal

help from the shoulder, or it's caught up in the geometry of neck,

jaw and collarbone. The shoulder pad can make the fiddle effectively

thicker, so that catching it under your jaw while it simultaneously rests

against the neck and collar bone may be easier. Some people report

that while they can hold the fiddle up without a shoulder pad, it's enough

easier with it that they prefer to use one. Most people are probably

better off with one, but if you're one of the exceptions, it's worth finding

out.